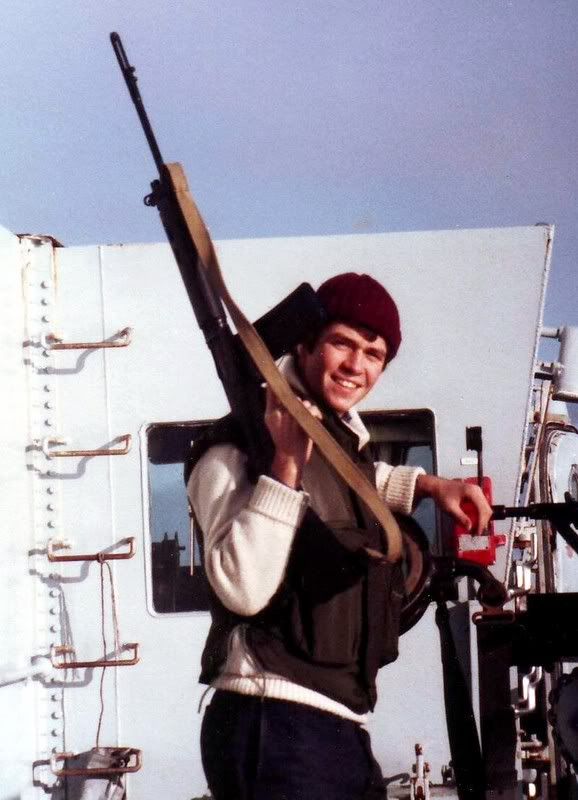

Derribo/shoot down Garcia Cuerva

», los historiadores aeronáuticos cuentan la partida de dos Mirage III de la escuadrilla «Dardo», piloteados por su guía, el Capitán Gustavo García Cuerva y su numeral o acompañante, el Primer Teniente C.E.Perona. Matassi explica que «se trabaron en combate con dos Sea Harrier del portaviones HMS Invincible, al norte de nuestra Isla Gran Malvina». Después que el numeral fue atacado y logró eyectarse, el guía habría avistado al otro portaaviones, el HMS Hermes, «unas 25 millas al este de Puerto Argentino. García Cuerva picó sobre el buque insignia y lo atacó con lo que le restaba: sus cañones de 30 milímetros», después de lo cual ya no contaba con suficiente combustible para regresar a su base en Patagonia. Fue entonces cuando solicitó autorización para aterrizar en la base aérea de Puerto Argentino. Pero le fue denegada, y se lo instó a eyectarse. Dos historiadores de la FAA narran lo ocurrido del siguiente modo:

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

García Cuerva contestó «tengo el avión intacto, avisen a la artillería antiaérea que voy a aterrizar». Se le ordenó dos veces más que debía eyectarse, desoyó la orden, entró en el corredor y al arrojar sus cargas externas para tener el avión limpio para el aterrizaje, fue abatido por la artillería propia, cayendo al Sur de la península de Frecynet, en el mar, próximo a las rocas de Maggie Elliot, siendo las 16:38 hs (Moro, 1985:181-2).

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

[...] él había decidido aterrizar en la BAM Malvinas. A él le pedían que abandonara -así como así- a su maravilloso avión... que funcionaba a la perfección... para que se estrellara, sin comandos... ¿por ahí...? ¡No... no! él podía aterrizarlo sin destruirlo... o dañándolo muy poco... no era un capricho suyo! [...] así que tomó la resolución de aterrizar en BAM Malvinas... ¡seguramente lo hubiera hecho impecablemente!

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

¡Pero nuestra inexperiencia de guerra! La artillería antiaérea desplegada alrededor de la Base, luego de haber recibido los primeros ataques de esta batalla (y qué ataques) y que por otras muchas razones, todavía no había logrado la compleja y serena coordinación necesaria para detectar en segundos un avión de guerra y determinar si es propio o enemigo. Ante la duda los artilleros lo consideraron enemigo... y lo derribaron en su aproximación final a la pista. Estos son los imponderables de la guerra... y su injusticia causa mucho dolor (Matassi, 1990:94-5).

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

El «friendly fire» es una figura común a todo teatro bélico. Matassi atribuye el derribo del M-III a la falta de experiencia conjunta en escenarios de combate. En este punto la falta de «inteligencia» como información era crucial. Pero la «inteligencia» como inteligibilidad recíproca entre armas y fuerzas proveía la segunda y casi inmediata lectura en una campaña que careció, por lo general, de coordinación cooperativa. Por eso, cuando Matassi describe la persecución de los Harrier a García Cuerva y a Perona, destaca que los Harrier de la misma PAC pertenecían a la aviación y a la marina británicas (1990:94, n.10). En este mismo sentido el cargo más recurrente que recibió la FAA por su desempeño en Malvinas fue haber actuado «con exceso de independencia respecto de los componentes del teatro» (CAERCAS, 1988; Costa, 1988:124), prescindiendo de la información procedente de otras fuerzas y eligiendo los blancos desde el comando de la Fuerza Aérea Sur, al mando del Brigadier Crespo por propia iniciativa y según sus prioridades. Para Matassi el piloto derribado había sido víctima de la ausencia de coordinación de sus compatriotas ofreciendo a cambio preservar el bien más preciado de la fuerza, su avión. Así, para su caída prematura y sin sentido, Matassi destacaba a García Cuerva como el primer argentino que bombardeara un blanco de tal importancia que permaneció como objetivo de la aviación aeronáutica y naval durante la campaña: el portaaviones HMS Hermes. Sus presuntos daños no fueron reconocidos por Gran Bretaña.

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

La descripción de las operaciones restantes de la jornada, algunas con final trágico, permiten restituir el derribo de García Cuerva al campo internacional en una guerra tecnológicamente desigual. El Primer Teniente Ardiles era derribado en su solitario M-V de la escuadrilla «Rubio», por un Sidewinder, tras cañonear algunos buques (Matassi, 1990:96; Moro, 1985:182). En el llamado «segundo ataque» la escuadrilla «Torno» de tres M-V comandados por el Capitán N.R.Dimeglio, atacó un destructor y dos fragatas -presuntamente el Exeter, la Alacrity y la Arrow, según la interpretación argentina. Por último dos secciones de Canberra MK-62 que se lanzaron sobre un grupo de buques y el portaaviones «Invincible», fueron interceptados por una PAC de Harriers que abatió a un avión con sus dos tripulantes (Matassi, 1990:96; Moro, 1985:182).

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

El éxito de las aproximadamente 30 salidas era bastante relativo. El enemigo había obtenido una respuesta que, sin embargo, no era todo lo contundente que las historias institucionales sugieren. Pero la FAA y sus historiadores lograban dar relieve a los intentos convirtiéndolos en pequeñas y aleccionadoras hazañas de aquel primer eslabón, el 1º de mayo, en aquella «larga y gloriosa cadena de victorias y sacrificios» (Clarín 2/5/83).

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>------------------------------------------------------------------------------

<!--[if !supportEmptyParas]--> <!--[endif]--><o> </o>

"Aeronautical historians have the departure of two of the Mirage III squadron 'Dart', piloted by your guide, Captain Gustavo Garcia Cuerva or numeral and its companion, First Lieutenant CEPerona. Matassi explains that it "engaged in combat with two of the Sea Harrier aircraft carrier HMS Invincible, to the north of our island Malvina Major. After the paragraph was attacked and managed to eject, the guide would have sighted the other aircraft carrier, HMS Hermes, "about 25 miles east of Puerto Argentino. Garcia Cuerva stung on the flagship and attacked him with what remained: its 30 mm cannon, after which no longer had enough fuel to return to their base in Patagonia. Then when he asked permission to land at the airbase of Puerto Argentino. But he was refused, and urged him to eject. Two historians tell the FAA what happened as follows:

Garcia Cuerva replied "I have the plane intact, antiaircraft artillery tell I'm going to land." He was ordered to be twice as eject, ignored the order, came into the corridor and to shed their external loads to take the plane to land clean, was killed by the artillery itself, falling on the southern peninsula Frecynet in the sea near the rocks of Maggie Elliot, being 16:38 pm (Moro, 1985:181-2).

[...] He had decided to land in the BAM Malvinas. He was asked to leave as well as well-a wonderful plane ... worked to perfection ... for the crash, without commands ... Why ... why? No. ..! no! he could land without destroying it ... damaged or very little ... theirs was not a whim! [...] So we took the decision to land at BAM Malvinas ... ¡Surely would have done impeccably!

But our inexperience of war! Antiaircraft artillery deployed around the base, after having received the first attack of this battle (and what attacks) and for many other reasons, had not yet achieved the necessary coordination complex and serene in seconds for a plane of war and determine whether their own or enemy. When in doubt it as the enemy gunners ... demolished and in its final approach to the runway. These are the imponderables of war ... injustice and cause much pain (Matassi, 1990:94-5).

The "friendly fire" is a figure common to the entire theater of war. Matassi attributed the fall of M-III to the lack of joint experience in combat scenarios. At this point the lack of intelligence information was crucial. But the intelligence and mutual intelligibility between weapons and forces provided almost immediate and the second reading in a campaign that lacked, in general, coordinating cooperative. So when Matassi describes the persecution of the Harrier and Perona Garcia Cuerva stresses that of the Harrier CAP aircraft already owned by the British Navy (1990:94, n.10). In this sense, the most common charge that the FAA has received for his performance in the Malvinas was acting "in excess of independence of the components of the theater" (CAERCAS, 1988; Costa, 1988:124), regardless of the information from other forces and choosing targets from the command of the Air Force South, commanded by Brigadier Crespo on their own initiative and according to their priorities. Matassi for the downed pilot had suffered a lack of coordination of his countrymen by offering in return to preserve the most precious of force, its aircraft. So, for his downfall and untimely end, Garcia stressed Matassi Cuerva as the first Argentine to bomb a target of such importance that it remained a target aircraft and naval aviation during the campaign: the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes. His alleged damages were not recognized by Britain.

The description of the remaining operations of the day, some with a tragic end, allow the demolition of returning to Camp Garcia Cuerva into an international war technologically diverse. First Lieutenant Ardiles was shot down in his lone squadron of MV "Blonde" by a Sidewinder, after fees vessels (Matassi, 1990:96; Moro 1985:182). In the 'second attack' squadron 'Torno' three MV commanded by Captain NRDimeglio attacked a destroyer and two frigates-the allegedly Exeter, the Alacrity and Arrow, according to the Argentine. Last two sections of Canberra MK-62 is launched on a group of ships and aircraft carrier 'Invincible', were intercepted by a CAP Harriers that befell a plane with two crew (Matassi, 1990:96; Moro, 1985 : 182).

The success of the about 30 exits was quite concerning. The enemy had received a reply which, however, was not all that strong institutional histories suggest. But the FAA and its historians managed to highlight the attempts and making them small feats instructive that first step, on 1 May, at the "long and glorious string of victories and sacrifices" (Clarín 2/5/83).<o>

Author: </o><meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8"><meta name="ProgId" content="Word.Document"><meta name="Generator" content="Microsoft Word 9"><meta name="Originator" content="Microsoft Word 9"><link rel="File-List" href="file:///C:/DOCUME%7E1/ADMINI%7E1/CONFIG%7E1/Temp/msoclip1/05/clip_filelist.xml"><!--[if gte mso 9]><xml> <w:WordDocument> <w:View>Normal</w:View> <w:Zoom>0</w:Zoom> <w:HyphenationZone>21</w:HyphenationZone> <w

oNotOptimizeForBrowser/> </w:WordDocument> </xml><![endif]--><style> <!-- /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:70.85pt 3.0cm 70.85pt 3.0cm; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} --> </style>[FONT="]Rosana Guber, Ph.D. y M.A. en Antropología (Johns Hopkins University, Estados Unidos) y máster en Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO, Buenos Aires). Investigadora del CONICET-Argentina, directora del Centro de Antropología Social del Instituto de Desarrollo Económico y Social IDES, Argentina, y coordinadora académica de la Maestría en Antropología Social IDES/IDAES, Universidad Nacional de General San Martín[/FONT]

oNotOptimizeForBrowser/> </w:WordDocument> </xml><![endif]--><style> <!-- /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:70.85pt 3.0cm 70.85pt 3.0cm; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} --> </style>[FONT="]Rosana Guber, Ph.D. y M.A. en Antropología (Johns Hopkins University, Estados Unidos) y máster en Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO, Buenos Aires). Investigadora del CONICET-Argentina, directora del Centro de Antropología Social del Instituto de Desarrollo Económico y Social IDES, Argentina, y coordinadora académica de la Maestría en Antropología Social IDES/IDAES, Universidad Nacional de General San Martín[/FONT]

oNotOptimizeForBrowser/> </w:WordDocument> </xml><![endif]--><style> <!-- /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:70.85pt 3.0cm 70.85pt 3.0cm; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} --> </style>[FONT="]Rosana Guber, Ph.D. y M.A. en Antropología (Johns Hopkins University, Estados Unidos) y máster en Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO, Buenos Aires). Investigadora del CONICET-Argentina, directora del Centro de Antropología Social del Instituto de Desarrollo Económico y Social IDES, Argentina, y coordinadora académica de la Maestría en Antropología Social IDES/IDAES, Universidad Nacional de General San Martín[/FONT]