DSV

Colaborador

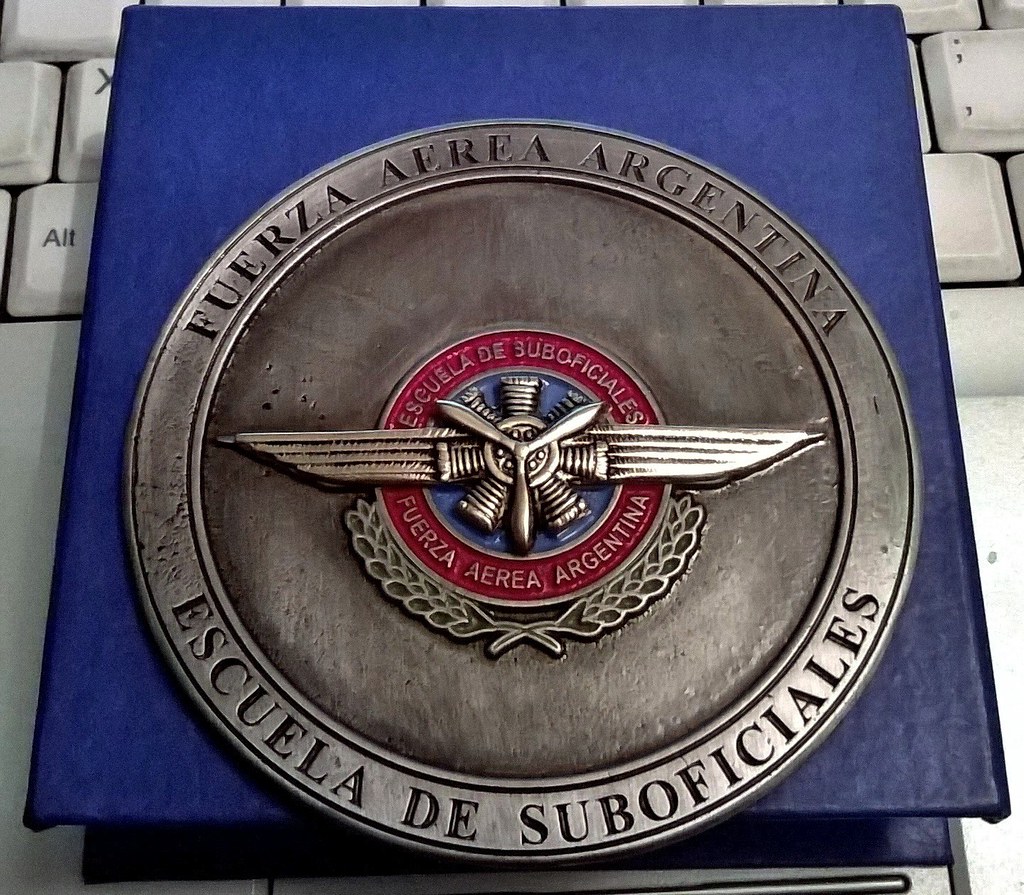

Argentine Air Force Trains Dogs for Security and Defense Tasks

The canines serve as an early warning system and are ready to engage in combat.

Eduardo Szklarz/Diálogo | 9 February 2018

Fausto, a Belgian Malinois trained to detect narcotics, poses with his guide from IFE's Dogs of War Section. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

The Argentine Air Force (FAA, in Spanish) counts with a special form of support: a group of dogs trained at Ezeiza Training Institute (IFE, in Spanish), 40 kilometers from the Argentine capital. The dogs work in concert with the unit’s security system, making rounds and patrols with their guides. They are also ready to go into combat. “Because of their visual, olfactory, and auditory abilities, dogs work like radar, detecting any noise or anomaly from miles away,” FAA Technical Sergeant Néstor González, an instructor and dog trainer at IFE’s Dogs of War Section, told Diálogo.

Technical Sergeant Néstor González (standing, fourth from left) stands with members of IFE’s Dogs of War Section. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

According to Tech. Sgt. González, the animals serve in two ways: primary value and secondary value. Their primary value is to detect and alert the unit of any presumed threat—which might be, for example, a group of people trying to enter the perimeter of the unit to cause damage. “And their secondary value is to deter, repel, and—as a last resort—apprehend and attack,” he explained.

FAA Colonel Rodolfo R. Etchegaray, head of IFE Core Group, toldDiálogo that canine training provides for a fully integrated security system. “In other words, we can set it up with human resources, animals, and technology,” Col. Etchegaray said. “The dogs serve as early warning for the entire Defense and Security System.”

According to Col. Etchegaray, owning dogs trained in such duties offers clear advantages. They can detect an intruder before the human resource or technological asset can. They don't get bored and they don’t fall asleep. They’re always alert and on guard. And their training and upkeep are more affordable than those of human beings and/or technological systems.

Full effectiveness

Every night, dogs head out with their guides and rifleman to make their rounds. “In general, we start at 22:00 hours and we finish just before 6 in the morning. Every two hours, we make a round of the perimeter and the internal facilities,” Tech. Sgt. González said. “Dogs are vital to look after the unit’s sensitive areas, such as the weapons room and the companies where candidates are housed,” he said.

“The dog can detect a person approaching by foot, or crawling, from a distance of up to 2 kilometers, and can also detect noises from cars, airplanes, and alarms up to 5 or 6 kilometers away,” the instructor said. If it detects any anomaly, the dog alerts its guide. It usually barks and turns its head, indicating that there’s something in that direction. “Once the dog enters into a combat situation and its sight, smell, and hearing start functioning in a synchronized manner, the accuracy of what it hears is 99.9 percent at long distances, day or night.”

“In the event we have to operate on a battlefield, the dog is ready to do patrols, provide early warning, and engage in close personal combat with their guide,” Tech. Sgt. González explained. “We do field work and attack and defense drills in the water, at high elevations—wherever. The dog is ready.”

Training stages

Roco, IFE’s German shepherd, trains in attacking an alleged offender. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

IFE’s Dogs of War Section has eight animals, including Roco, a German shepherd; Shina, a Brazilian mastiff; and Fausto, a Belgian Malinois trained to detect narcotics. The training consists of three stages: basic, advanced, and tactical. During basic training, the animal learns to walk with the guide and to sit, stay, lie down, and play dead, among other commands. These tasks are performed using a leash to guide the dog and a choke collar to discipline it.

In the more rigorous advanced stage, the animal is trained for agility and dexterity skills, such as jumping fences, climbing stairs, and going through obstacles, using only a short or long leash. In both initial stages, the dog is trained to attack. It learns to detect offenders. For that training, a decoy is used—a person in protective clothing who acts suspiciously.

“For the dog, it’s rewarding to know that it did a good job. It knows that its guide will reward it with positive reinforcement, either a 'Well done!’ and a pat, or a treat that it likes,” Tech. Sgt. González said. Finally, in the tactical phase, the dog works solo, acting on voice commands. All three stages take about a year, but the training continues on a daily basis.

“We have to be cognizant of how we will use the commands based on the type of threat. For example, if an unarmed person enters the unit, we’ll use the dog to deter him by barking,” Tech. Sgt. González explained. “But if there is any real danger of a confrontation between the offender and us, we’ll shift to action and apprehension. And if our lives are at risk, we teach the dog to approach and bite the person.”

The animal is trained to disarm the aggressor, but will also look after him when service members demand it. “We use the dog carefully. We also need to protect the life of the offender,” the trainer said.

Early warning

IFE’s dogs can even detect members of special commands. “Elite groups from forces all over the world can get out of any conflict location or overcome any unit or human resource. But things get more complicated for them when they have to operate in a place where there is an early-warning dog, because the dog will detect them,” Tech. Sgt. González said.

“When they attempt to attack a place or overtake it, such groups do so by helicopter or crawling on the ground. But even with the slightest movement of their elbow, the dog detects them,” he said. “We’ve verified that at night, in the cold, and in wind, rain, and heat. The dog detects them.”

Exchange with the United States

In September 2017, Tech. Sgt. González and other leaders of FAA’s canine sections participated in a Working Methods Exchange seminar held by the 4th Air Brigade in El Plumerillo, in the province of Mendoza, Argentina, together with one officer and two noncommissioned officers from the U.S. Air Force K-9 Handler School. “For one week, we exchanged working methods and kept up an ongoing dialog on how we operate with our dogs,” Tech. Sgt. González said. “Our take-away was that our working methods are very similar, but that there is a difference in terms of resources.”

https://dialogo-americas.com/en/articles/argentine-air-force-trains-dogs-security-and-defense-tasks

The canines serve as an early warning system and are ready to engage in combat.

Eduardo Szklarz/Diálogo | 9 February 2018

Fausto, a Belgian Malinois trained to detect narcotics, poses with his guide from IFE's Dogs of War Section. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

The Argentine Air Force (FAA, in Spanish) counts with a special form of support: a group of dogs trained at Ezeiza Training Institute (IFE, in Spanish), 40 kilometers from the Argentine capital. The dogs work in concert with the unit’s security system, making rounds and patrols with their guides. They are also ready to go into combat. “Because of their visual, olfactory, and auditory abilities, dogs work like radar, detecting any noise or anomaly from miles away,” FAA Technical Sergeant Néstor González, an instructor and dog trainer at IFE’s Dogs of War Section, told Diálogo.

Technical Sergeant Néstor González (standing, fourth from left) stands with members of IFE’s Dogs of War Section. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

According to Tech. Sgt. González, the animals serve in two ways: primary value and secondary value. Their primary value is to detect and alert the unit of any presumed threat—which might be, for example, a group of people trying to enter the perimeter of the unit to cause damage. “And their secondary value is to deter, repel, and—as a last resort—apprehend and attack,” he explained.

FAA Colonel Rodolfo R. Etchegaray, head of IFE Core Group, toldDiálogo that canine training provides for a fully integrated security system. “In other words, we can set it up with human resources, animals, and technology,” Col. Etchegaray said. “The dogs serve as early warning for the entire Defense and Security System.”

According to Col. Etchegaray, owning dogs trained in such duties offers clear advantages. They can detect an intruder before the human resource or technological asset can. They don't get bored and they don’t fall asleep. They’re always alert and on guard. And their training and upkeep are more affordable than those of human beings and/or technological systems.

Full effectiveness

Every night, dogs head out with their guides and rifleman to make their rounds. “In general, we start at 22:00 hours and we finish just before 6 in the morning. Every two hours, we make a round of the perimeter and the internal facilities,” Tech. Sgt. González said. “Dogs are vital to look after the unit’s sensitive areas, such as the weapons room and the companies where candidates are housed,” he said.

“The dog can detect a person approaching by foot, or crawling, from a distance of up to 2 kilometers, and can also detect noises from cars, airplanes, and alarms up to 5 or 6 kilometers away,” the instructor said. If it detects any anomaly, the dog alerts its guide. It usually barks and turns its head, indicating that there’s something in that direction. “Once the dog enters into a combat situation and its sight, smell, and hearing start functioning in a synchronized manner, the accuracy of what it hears is 99.9 percent at long distances, day or night.”

“In the event we have to operate on a battlefield, the dog is ready to do patrols, provide early warning, and engage in close personal combat with their guide,” Tech. Sgt. González explained. “We do field work and attack and defense drills in the water, at high elevations—wherever. The dog is ready.”

Training stages

Roco, IFE’s German shepherd, trains in attacking an alleged offender. (Photo: Eduardo Szklarz, Diálogo)

IFE’s Dogs of War Section has eight animals, including Roco, a German shepherd; Shina, a Brazilian mastiff; and Fausto, a Belgian Malinois trained to detect narcotics. The training consists of three stages: basic, advanced, and tactical. During basic training, the animal learns to walk with the guide and to sit, stay, lie down, and play dead, among other commands. These tasks are performed using a leash to guide the dog and a choke collar to discipline it.

In the more rigorous advanced stage, the animal is trained for agility and dexterity skills, such as jumping fences, climbing stairs, and going through obstacles, using only a short or long leash. In both initial stages, the dog is trained to attack. It learns to detect offenders. For that training, a decoy is used—a person in protective clothing who acts suspiciously.

“For the dog, it’s rewarding to know that it did a good job. It knows that its guide will reward it with positive reinforcement, either a 'Well done!’ and a pat, or a treat that it likes,” Tech. Sgt. González said. Finally, in the tactical phase, the dog works solo, acting on voice commands. All three stages take about a year, but the training continues on a daily basis.

“We have to be cognizant of how we will use the commands based on the type of threat. For example, if an unarmed person enters the unit, we’ll use the dog to deter him by barking,” Tech. Sgt. González explained. “But if there is any real danger of a confrontation between the offender and us, we’ll shift to action and apprehension. And if our lives are at risk, we teach the dog to approach and bite the person.”

The animal is trained to disarm the aggressor, but will also look after him when service members demand it. “We use the dog carefully. We also need to protect the life of the offender,” the trainer said.

Early warning

IFE’s dogs can even detect members of special commands. “Elite groups from forces all over the world can get out of any conflict location or overcome any unit or human resource. But things get more complicated for them when they have to operate in a place where there is an early-warning dog, because the dog will detect them,” Tech. Sgt. González said.

“When they attempt to attack a place or overtake it, such groups do so by helicopter or crawling on the ground. But even with the slightest movement of their elbow, the dog detects them,” he said. “We’ve verified that at night, in the cold, and in wind, rain, and heat. The dog detects them.”

Exchange with the United States

In September 2017, Tech. Sgt. González and other leaders of FAA’s canine sections participated in a Working Methods Exchange seminar held by the 4th Air Brigade in El Plumerillo, in the province of Mendoza, Argentina, together with one officer and two noncommissioned officers from the U.S. Air Force K-9 Handler School. “For one week, we exchanged working methods and kept up an ongoing dialog on how we operate with our dogs,” Tech. Sgt. González said. “Our take-away was that our working methods are very similar, but that there is a difference in terms of resources.”

https://dialogo-americas.com/en/articles/argentine-air-force-trains-dogs-security-and-defense-tasks

iz en el upgrade de cabina realizado en FADEA,mantiene por ahora el esquema SEA.

iz en el upgrade de cabina realizado en FADEA,mantiene por ahora el esquema SEA.