-

Aviso de importancia, Reglamento del Foro actualizado. Reglas Técnicas, punto Q. Ir al siguiente link: Ver aviso

Estás usando un navegador obsoleto. No se pueden mostrar estos u otros sitios web correctamente.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Noticias de la Armada de Estados Unidos

- Tema iniciado Guitro01

- Fecha de inicio

Que mole por Dios!

La Armada estadounidense hará un traje de Iron Man real

Se encuentra desarrollando a TALOS, una indumentaria ligera de asalto táctico (Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit)

Marvel

Fotograma de Iron Man 3

La tecnología presente en Iron Man poco a poco se hace realidad. La Armada estadounidense ha encargado desarrollar un traje ligero de asalto táctico (TALOS por su nombre en inglés), que provee al militar de habilidades como visión nocturna, protección antibalas y aumento de la fuerza.

Cada traje, como se ha indicado, tiene un sistema computarizado que es capaz de responder al instante a cierto tipo de situaciones o servir de alerta al soldado.

Según un comunicado de prensa, el Instituto de Tecnología de Massachusetts se encuentra trabajando en el desarrollo del material en el que traje estará confeccionado. La armadura será «líquida», con una compuesto que podrá pasar al «estado sólido» en milisegundos cuando se aplique un campo magnético o corriente eléctrica.

La idea es que sea un material a prueba de balas, con el que el soldado pueda entrar en una zona problemática sin que los disparos afecten su táctica. El traje también se encargaría de medir la temperatura de la piel, la tensión arterial, el rtimo cardíaco y los niveles de hidratación.

Un comando de operaciones especiales de los Estados Unidos se ha aliado con universidades, laboratorios y otras industrias para hacer posible esta idea.

El almirante Bill McRaven, encargado de desvelar la idea en una conferencia, señaló que la idea no se puso sobre la mesa después de ver Iron Man o leer el cómic. Fue debido a la muerte de miembros de sus tropas en Afganistán.

«Uno de los nuestros atravesó las puertas y fue asesinado por un Taliban que estaba del otro lado, él intentaba rescatar a un rehén», dijo McRaven,en esa ocasión. El almirante apunta que el traje «tiene una avanzada armadura, una fuente de alimentación, esqueletos prácticos...y diferentes tecnología de pantallas». Eso sí, TALOS no será capaz de volar. «No estamos con el traje volador de Iron Man», dijo.

Talos es también el nombre de un gigante de bronce de la mitología griega, encargado de proteger a la Creta minoica de posibles invasores

ABC.es

Se encuentra desarrollando a TALOS, una indumentaria ligera de asalto táctico (Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit)

Marvel

Fotograma de Iron Man 3

La tecnología presente en Iron Man poco a poco se hace realidad. La Armada estadounidense ha encargado desarrollar un traje ligero de asalto táctico (TALOS por su nombre en inglés), que provee al militar de habilidades como visión nocturna, protección antibalas y aumento de la fuerza.

Cada traje, como se ha indicado, tiene un sistema computarizado que es capaz de responder al instante a cierto tipo de situaciones o servir de alerta al soldado.

Según un comunicado de prensa, el Instituto de Tecnología de Massachusetts se encuentra trabajando en el desarrollo del material en el que traje estará confeccionado. La armadura será «líquida», con una compuesto que podrá pasar al «estado sólido» en milisegundos cuando se aplique un campo magnético o corriente eléctrica.

La idea es que sea un material a prueba de balas, con el que el soldado pueda entrar en una zona problemática sin que los disparos afecten su táctica. El traje también se encargaría de medir la temperatura de la piel, la tensión arterial, el rtimo cardíaco y los niveles de hidratación.

Un comando de operaciones especiales de los Estados Unidos se ha aliado con universidades, laboratorios y otras industrias para hacer posible esta idea.

El almirante Bill McRaven, encargado de desvelar la idea en una conferencia, señaló que la idea no se puso sobre la mesa después de ver Iron Man o leer el cómic. Fue debido a la muerte de miembros de sus tropas en Afganistán.

«Uno de los nuestros atravesó las puertas y fue asesinado por un Taliban que estaba del otro lado, él intentaba rescatar a un rehén», dijo McRaven,en esa ocasión. El almirante apunta que el traje «tiene una avanzada armadura, una fuente de alimentación, esqueletos prácticos...y diferentes tecnología de pantallas». Eso sí, TALOS no será capaz de volar. «No estamos con el traje volador de Iron Man», dijo.

Talos es también el nombre de un gigante de bronce de la mitología griega, encargado de proteger a la Creta minoica de posibles invasores

ABC.es

Gustaria de mandar mis felicitaciones por lo cumpleaños 238 de la US NAVY...

Es... horrible.

ALGO MAS DEL BARCO QUE LE GUSTA A NOCTURNO CULTO

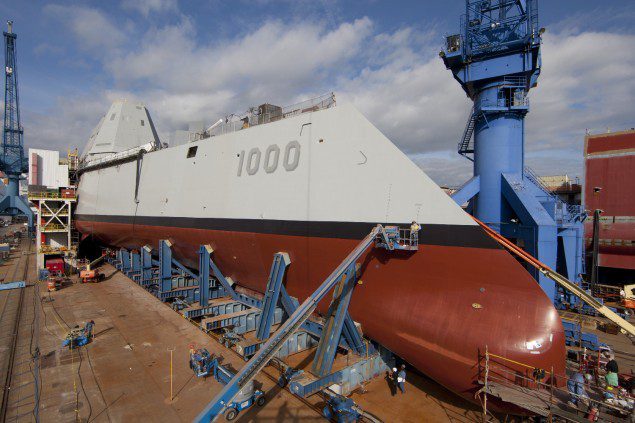

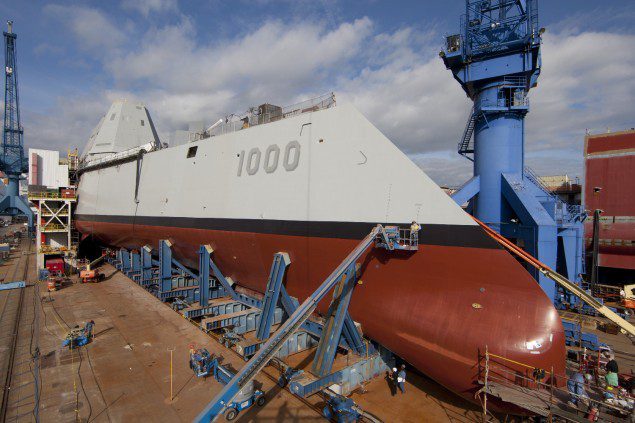

DDG 1000 Pics: Billy Badass Has Arrived

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Due to the US government shutdown over the past few weeks, the christening of the US Navy and General Dynamics-Bath Iron Works’ latest creation, DDG 1000 (soon to be USS Zumwalt) was unfortunately put on hold.

The good news is, Bath Iron Works shipyard, located in the great state of Maine – home of lobsters, pine trees, and Shipyard Ale – released the following images of this incredible ship, with lines that probably haven’t been seen on a ship since the 19th century.

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Don’t let the reverse sheer on this ship fool you though. Underneath its composite deckhouse (yes, that’s right) is the most sophisticated surface warfare battle suite ever installed on a warship that is tied into an array of weapon systems, including (but not limited to) twenty MK 57 vertical launch modules and a pair of 155 mm guns.

These guns have water-cooled barrels capable of hitting targets up to 83 nautical miles away at 10 rounds per minute.

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

This 600-foot, $3.3 BILLION warship is powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Marine Trent-30 gas turbines.

Image courtesy US Navy/General

DDG 1000 Pics: Billy Badass Has Arrived

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Due to the US government shutdown over the past few weeks, the christening of the US Navy and General Dynamics-Bath Iron Works’ latest creation, DDG 1000 (soon to be USS Zumwalt) was unfortunately put on hold.

The good news is, Bath Iron Works shipyard, located in the great state of Maine – home of lobsters, pine trees, and Shipyard Ale – released the following images of this incredible ship, with lines that probably haven’t been seen on a ship since the 19th century.

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Don’t let the reverse sheer on this ship fool you though. Underneath its composite deckhouse (yes, that’s right) is the most sophisticated surface warfare battle suite ever installed on a warship that is tied into an array of weapon systems, including (but not limited to) twenty MK 57 vertical launch modules and a pair of 155 mm guns.

These guns have water-cooled barrels capable of hitting targets up to 83 nautical miles away at 10 rounds per minute.

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

Image courtesy US Navy/General Dynamics Bath Iron Works/Michael C. Nutter

This 600-foot, $3.3 BILLION warship is powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Marine Trent-30 gas turbines.

Image courtesy US Navy/General

SOUTH CHINA SEA (Oct. 25, 2013) The U.S. Navy's forward-deployed aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73), top, transits alongside the Royal Malaysian navy Kedah-class offshore patrol vessel KD Pahang (172), the Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruiser USS Antietam (CG 54), and the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS McCampbell (DDG 85) during a training exercise. George Washington and its embarked air wing, Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 5, provide a combat-ready force that protects and defends the collective maritime interest of the U.S. and its allies and partners in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Liam Kennedy/Released)

La verdad a mi siempre me gustaron mucho los buques norteamericanos post WW II........

destructores tipo Coontz, Charles Adams,cruceros tipo Virginia,destructores Spruance, cruceros Ticonderoga, fragatas tipo García, Knox, Perry...............

pero ESTO ES DEMASIADO......

alguien podría explicarme qué sentido tiene la roda invertida, TAN INVERTIDAA....??

me parece que los diseñadores estuvieron de visita en el museo de la Guerra de Secesión no?

ojalá les sea útil a los norteamericanos este buque ( caro es...!!!!)

pero es definitivamente un bodoque estético,feísimo,espantosoooo......!!

destructores tipo Coontz, Charles Adams,cruceros tipo Virginia,destructores Spruance, cruceros Ticonderoga, fragatas tipo García, Knox, Perry...............

pero ESTO ES DEMASIADO......

alguien podría explicarme qué sentido tiene la roda invertida, TAN INVERTIDAA....??

me parece que los diseñadores estuvieron de visita en el museo de la Guerra de Secesión no?

ojalá les sea útil a los norteamericanos este buque ( caro es...!!!!)

pero es definitivamente un bodoque estético,feísimo,espantosoooo......!!

Commentary: Missing the Lesson of DDG 1000

As the US Navy prepares to christen the lead Zumwalt-class destroyer, DDG 1000, it would be useful to review the program’s history and evaluate past and present decisions. Critics of the value of a gunship to a Navy of the future completely missed the big picture. Building on the vision of prior chiefs of naval operations, Adm. Vern Clark described a future Navy with more efficient and more survivable destroyers and cruisers. What happened along the way?

■ Technology. Skeptics were concerned about a ship that relied on several new technologies: automated fire suppression to enable smaller crews, electric drive for fuel efficiency and electrical power, stealth, acoustic quieting, infrared suppression, etc. However, the DD(X) program — before its name was changed to DDG 1000 — was well-structured and relied on engineering development models for all of the key systems.

Despite projections from critics, DDG 1000 has delivered multiple new technologies without the cost growth associated with other DoD development programs. The program has confirmed the importance of technology maturation and prototyping.

■ Operational requirement. Many people questioned the utility of a gunship in modern warfare. Advocates promoted smaller ships for interdiction and coastal missions while others focused on sea-based missile defense. These discussions culminated in a meeting between Navy Secretary Gordon England, Clark, Defense Undersecretary Edward Aldridge and myself, which birthed the coherent long-term plan for LCS, DD(X) and CGX.

Importantly, DD(X) would provide the defensive support needed in littoral environments by a lower-cost littoral combat ship (LCS) with no defensive capability. The DD(X) hull would also evolve into a future cruiser.

■ Industrial base. DDG 1000 is a large ship, roughly 15,000 tons. The additional size and the refined finish to lower the radar signature require more construction labor hours. The ship was estimated to take about 7 million man hours at rate production compared with roughly 3 million for the 9,000-ton DDG 51-class destroyer.

DDG 51s were built at roughly three to five ships per year to meet early Navy inventory requirements and to efficiently load shipyards. DDG 51 production rates of one to two ships per year are inefficient and inadequate for the industrial base. The manufacturing labor required for DD(X), and the future CG(X), suggested that one ship per year could provide adequate labor loading for two destroyer yards.

Thus, there was a coherent and carefully considered strategy that favored DD(X) as a key element of a long-term plan for a Navy shipbuilding program. The DD(X) program would create a new hull design that reduced acoustic, radar and infrared signatures, meeting the demand for the Navy to operate in the near-shore environment and providing survivability against future threats.

The DD(X) hull provided growth capacity, supporting larger radars necessary for evolving missile defense missions.

The plan was largely derailed by a coalition of pundits who bear no responsibility for the nation’s future naval capability and garner attention through sensational forecasts. The Government Accountability Office, the Congressional Budget Office and the Congressional Research Service all forecast a $5 billion DDG 1000 destroyer. Acting on these assertions, and possibly concerned about buying gunships, the Navy changed course and decided to restart DDG 51 production. Let’s review these forecasts and decisions.

Bath Iron Works has done a remarkable job building the lead DDG 1000. The lead hull will not be anywhere near $5 billion. There is a prospect that a rate-production DDG 1000 could be $2.3 billion, roughly the price forecast in the early days of the program.

In contrast, after buying the final DDG 51s under a multiyear contract at about $1.2 billion per copy, the first new production-restart DDG 51 will cost about $2 billion. The DDG 51 restart adds to a full inventory of hulls that are well-suited to blue-water naval battles and ill-suited to providing defensive cover for LCS or helping the Navy conduct operations in a coastal environment.

The last part of the coherent plan was to remove the guns from the DDG 1000 hull and add more vertical launch tubes to create a new cruiser offering a much smaller crew, stealth, quietness, fuel efficiency and growth. The electric drive system offered the potential to support electromagnetic weapons — game changers in terms of range, speed and offensive and defensive capability.

Restarting the DDG 51 program provides none of these benefits, nor a path to a cruiser.

Further, the Navy will probably need to build three DDG 51s per year to provide affordable prices and stable workload for two destroyer yards.

The course change undermined a coherent, long-term naval strategy that sought to provide the Navy with the capability to execute missions in a hostile littoral environment, to evolve to a fleet of more survivable and capable cruisers, and to sustain a stable industrial base. Sensational projections about DD(X) technical risk and cost have proved inaccurate.

There may still be time for the Navy to review these decisions as they learn from the highly capable new DDG 1000 destroyer.

John Young is a senior fellow and member of the board of regents at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. He previously served as the US Navy’s assistant secretary for research, development and acquisition, and he is currently the principal in JY Strategies LLC.

As the US Navy prepares to christen the lead Zumwalt-class destroyer, DDG 1000, it would be useful to review the program’s history and evaluate past and present decisions. Critics of the value of a gunship to a Navy of the future completely missed the big picture. Building on the vision of prior chiefs of naval operations, Adm. Vern Clark described a future Navy with more efficient and more survivable destroyers and cruisers. What happened along the way?

■ Technology. Skeptics were concerned about a ship that relied on several new technologies: automated fire suppression to enable smaller crews, electric drive for fuel efficiency and electrical power, stealth, acoustic quieting, infrared suppression, etc. However, the DD(X) program — before its name was changed to DDG 1000 — was well-structured and relied on engineering development models for all of the key systems.

Despite projections from critics, DDG 1000 has delivered multiple new technologies without the cost growth associated with other DoD development programs. The program has confirmed the importance of technology maturation and prototyping.

■ Operational requirement. Many people questioned the utility of a gunship in modern warfare. Advocates promoted smaller ships for interdiction and coastal missions while others focused on sea-based missile defense. These discussions culminated in a meeting between Navy Secretary Gordon England, Clark, Defense Undersecretary Edward Aldridge and myself, which birthed the coherent long-term plan for LCS, DD(X) and CGX.

Importantly, DD(X) would provide the defensive support needed in littoral environments by a lower-cost littoral combat ship (LCS) with no defensive capability. The DD(X) hull would also evolve into a future cruiser.

■ Industrial base. DDG 1000 is a large ship, roughly 15,000 tons. The additional size and the refined finish to lower the radar signature require more construction labor hours. The ship was estimated to take about 7 million man hours at rate production compared with roughly 3 million for the 9,000-ton DDG 51-class destroyer.

DDG 51s were built at roughly three to five ships per year to meet early Navy inventory requirements and to efficiently load shipyards. DDG 51 production rates of one to two ships per year are inefficient and inadequate for the industrial base. The manufacturing labor required for DD(X), and the future CG(X), suggested that one ship per year could provide adequate labor loading for two destroyer yards.

Thus, there was a coherent and carefully considered strategy that favored DD(X) as a key element of a long-term plan for a Navy shipbuilding program. The DD(X) program would create a new hull design that reduced acoustic, radar and infrared signatures, meeting the demand for the Navy to operate in the near-shore environment and providing survivability against future threats.

The DD(X) hull provided growth capacity, supporting larger radars necessary for evolving missile defense missions.

The plan was largely derailed by a coalition of pundits who bear no responsibility for the nation’s future naval capability and garner attention through sensational forecasts. The Government Accountability Office, the Congressional Budget Office and the Congressional Research Service all forecast a $5 billion DDG 1000 destroyer. Acting on these assertions, and possibly concerned about buying gunships, the Navy changed course and decided to restart DDG 51 production. Let’s review these forecasts and decisions.

Bath Iron Works has done a remarkable job building the lead DDG 1000. The lead hull will not be anywhere near $5 billion. There is a prospect that a rate-production DDG 1000 could be $2.3 billion, roughly the price forecast in the early days of the program.

In contrast, after buying the final DDG 51s under a multiyear contract at about $1.2 billion per copy, the first new production-restart DDG 51 will cost about $2 billion. The DDG 51 restart adds to a full inventory of hulls that are well-suited to blue-water naval battles and ill-suited to providing defensive cover for LCS or helping the Navy conduct operations in a coastal environment.

The last part of the coherent plan was to remove the guns from the DDG 1000 hull and add more vertical launch tubes to create a new cruiser offering a much smaller crew, stealth, quietness, fuel efficiency and growth. The electric drive system offered the potential to support electromagnetic weapons — game changers in terms of range, speed and offensive and defensive capability.

Restarting the DDG 51 program provides none of these benefits, nor a path to a cruiser.

Further, the Navy will probably need to build three DDG 51s per year to provide affordable prices and stable workload for two destroyer yards.

The course change undermined a coherent, long-term naval strategy that sought to provide the Navy with the capability to execute missions in a hostile littoral environment, to evolve to a fleet of more survivable and capable cruisers, and to sustain a stable industrial base. Sensational projections about DD(X) technical risk and cost have proved inaccurate.

There may still be time for the Navy to review these decisions as they learn from the highly capable new DDG 1000 destroyer.

John Young is a senior fellow and member of the board of regents at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. He previously served as the US Navy’s assistant secretary for research, development and acquisition, and he is currently the principal in JY Strategies LLC.

Come aboard USS Gerald R Ford (CVN 78), the newest aircraft carrier

Una mirada poco común a tres portaaviones en Newport News Shipbuilding

El Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) se encuentra en el dique seco en Newport News Shipbuilding, en espera de su ceremonia de bautizo el 09 de noviembre.

It’s not every decade that a new aircraft carrier design comes along. But now, for the first time since the early 1970s, the first of a new class of nuclear-powered behemoths is being revealed to the public along the shores of the James River in Virginia.

The Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) is rising in a giant graving dock at the northwest end of the sprawling shipyard of Newport News Shipbuilding. Officially under construction since November 2009, the work to build the 1,092-fo0t-long ship has actually been going on for more than a decade. Hiding under scaffolding, covered in anti-rust primer, the Ford has just received a new coat of paint, part of the preparations for her public debut on Nov. 9, when ship’s sponsor Susan Ford Bales, daughter of the 38th U.S. president, will formally christen the ship.

Water was let into the dock to float the Ford for the first time on Oct. 11. She’s not yet officially launched — that won’t technically take place until after the christening ceremony when the ship is moved out of the dock to a fitting-out berth in the shipyard. The Ford isn’t anywhere near complete yet, either — the ship is scheduled to be delivered to the Navy in early 2016, and it will be some time after that before the ship is declared operational and ready to deploy.

Defense News was given a look at the ship on Oct. 22. While the outside of the hull is freshly painted, inside the Ford is swarming with a couple thousand shipbuilders. Staging and scaffolding abound in the hangar deck and around the ship’s island superstructure, and the flight deck is covered with temporary structures.

Elsewhere in the yard the Nimitz-class carrier Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) is half a year into a three-and-a-half-year refueling overhaul, which will also see most of the ship torn apart and refurbished. At the opposite end of the yard, the Enterprise (CVN 65), inactivated last December, is undergoing dismantlement. Built at Newport News and delivered in October 1961, the ship’s reactors are being defueled and and much equipment is being removed.

Newport News Shipbuilding, part of Huntington Ingalls Industries, is the only US shipyard capable of building a full-sized, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

We photographed each of the three carriers during our visit. Unless otherwise noted, all photos are by Christopher P. Cavas.

Una mirada poco común a tres portaaviones en Newport News Shipbuilding

El Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) se encuentra en el dique seco en Newport News Shipbuilding, en espera de su ceremonia de bautizo el 09 de noviembre.

It’s not every decade that a new aircraft carrier design comes along. But now, for the first time since the early 1970s, the first of a new class of nuclear-powered behemoths is being revealed to the public along the shores of the James River in Virginia.

The Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) is rising in a giant graving dock at the northwest end of the sprawling shipyard of Newport News Shipbuilding. Officially under construction since November 2009, the work to build the 1,092-fo0t-long ship has actually been going on for more than a decade. Hiding under scaffolding, covered in anti-rust primer, the Ford has just received a new coat of paint, part of the preparations for her public debut on Nov. 9, when ship’s sponsor Susan Ford Bales, daughter of the 38th U.S. president, will formally christen the ship.

Water was let into the dock to float the Ford for the first time on Oct. 11. She’s not yet officially launched — that won’t technically take place until after the christening ceremony when the ship is moved out of the dock to a fitting-out berth in the shipyard. The Ford isn’t anywhere near complete yet, either — the ship is scheduled to be delivered to the Navy in early 2016, and it will be some time after that before the ship is declared operational and ready to deploy.

Defense News was given a look at the ship on Oct. 22. While the outside of the hull is freshly painted, inside the Ford is swarming with a couple thousand shipbuilders. Staging and scaffolding abound in the hangar deck and around the ship’s island superstructure, and the flight deck is covered with temporary structures.

Elsewhere in the yard the Nimitz-class carrier Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) is half a year into a three-and-a-half-year refueling overhaul, which will also see most of the ship torn apart and refurbished. At the opposite end of the yard, the Enterprise (CVN 65), inactivated last December, is undergoing dismantlement. Built at Newport News and delivered in October 1961, the ship’s reactors are being defueled and and much equipment is being removed.

Newport News Shipbuilding, part of Huntington Ingalls Industries, is the only US shipyard capable of building a full-sized, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

We photographed each of the three carriers during our visit. Unless otherwise noted, all photos are by Christopher P. Cavas.

El Ford se encuentra en el dique seco en el extremo noroeste del astillero Newport News Shipbuilding. El muelle, lo suficientemente grande para contener dos portaaviones, fue construido originalmente para la construcción de buques comerciales, un negocio el astillero ya no maneja.

Los empleados del astillero en chalecos salvavidas están trabajando en una barcaza justo por delante de la nave, erigiendo la puesta en escena desde donde la patrocinadora de la nave Susan Ford Bales bautizará el portaaviones el 09 de noviembre

En la cubierta de vuelo, cobertizos protectores cubren tres de los cuatro sistemas(EMALS), una nueva tecnología que aparecerá por primera vez en los portaaviones de la clase Ford.

La sección delantera de la Ford cuenta con un gran bulbo de proa bajo el agua - una característica similar a la que equipó los dos últimos portadores de la clase Nimitz anterior. Sin embargo, el Ford también muestra un nudillo pronunciado hacia el interior a nivel de la cubierta del hangar - una característica, de acuerdo con los funcionarios del programa, destinada a reducir los costos haciendo el casco más simple de construir.

Temas similares

- Respuestas

- 9

- Visitas

- 1K

- Respuestas

- 0

- Visitas

- 1K